Visually Impaired KCS students are supported by Vision Team

Posted by Josh Flory

ETEnlightener/Health & Happiness

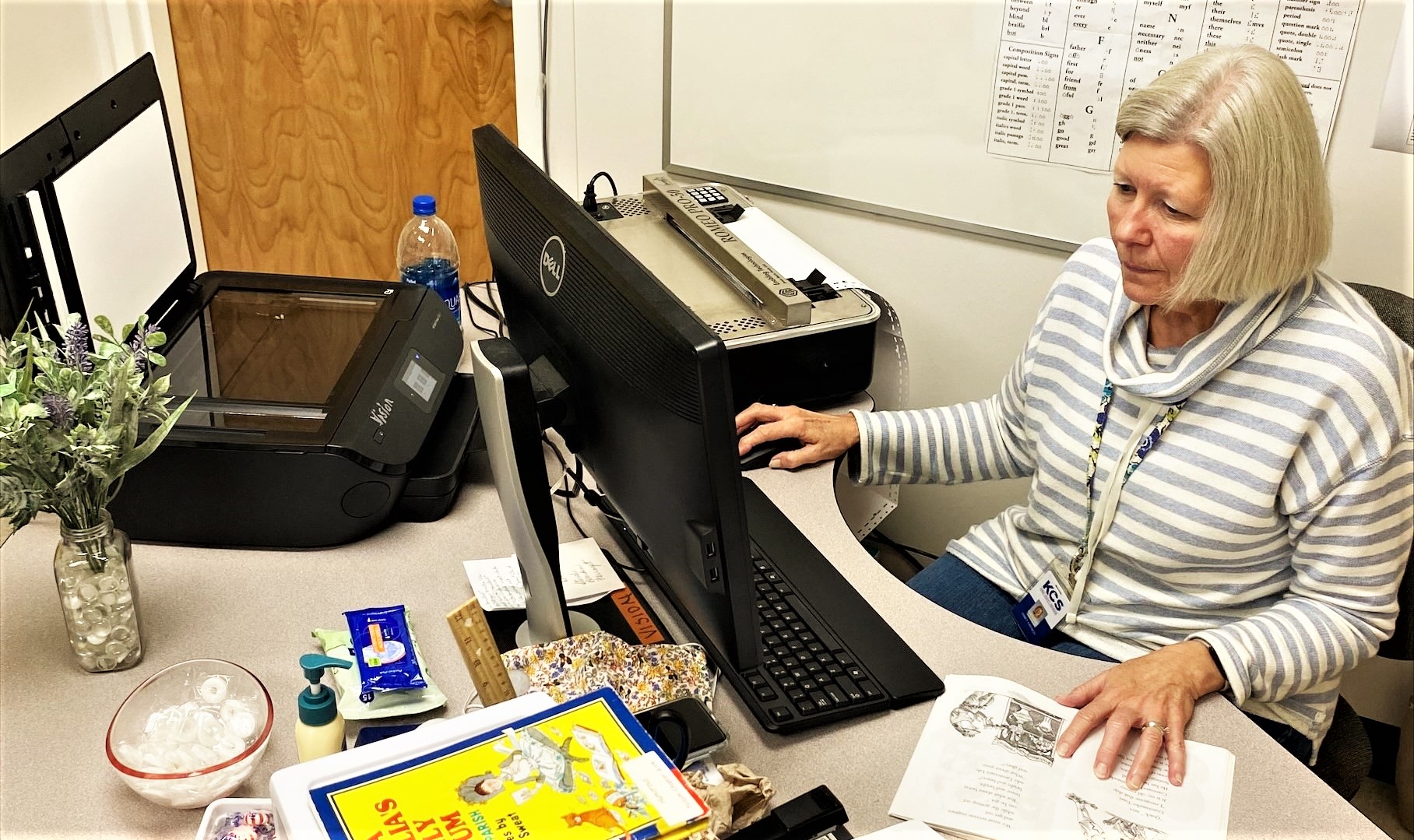

Knox County Schools (October 2021) – On a recent morning at Sterchi Elementary, Janet French took a one-page sheet of writing exercises and scanned them into her computer.

After making sure the worksheet was correct, she entered a command. A staccato noise like a miniature jackhammer rang out from a nearby printer as embossed pages unfurled from the device.

Several minutes later, French retrieved a six-page sheet of double-spaced braille pages from the printer, ready for use by a student at the school.

While the KCS Vision Department is a relatively small portion of the district’s overall workforce, braillists like French — along with KCS teachers of the visually impaired and orientation & mobility specialists — have a significant impact on approximately 150 blind or low-vision students in Knox County.

Mandi Taylor, a teacher of the visually impaired, said those students can use a wide range of tools that vary in degrees of technological complexity.

At one end of the spectrum are simple magnifying tools, such as a half-sphere “dome magnifier” for books or a telescope-like monocular to assist with viewing material at a distance, such as writing on a classroom whiteboard.

Digital tools are also available, such as closed-circuit TV devices that can display written material or the image of a teacher on a digital screen.

Braille, a writing system of raised dots on paper, is also a vital resource. Four district schools have dedicated braille stations; Sterchi, Farragut Middle, Carter High, and South-Doyle High. This resource is invaluable to allowing blind and visually impaired students to have equal access to assignments and resources.

Additional resources in braille include flashcards to practice math facts or other memorization tasks, and a tactical graphics kit can help teachers create materials by hand.

More advanced tools include the “Jaws” screen reader, which can read on-screen text out loud, and even a BrailleNote Touch tablet, in which braille dots pop up along a narrow strip at the bottom of the tablet as users scroll through the material.

Learning to read braille can take two years, and Taylor said the tools used by students might change over time, especially as they get older and take on different challenges.

Lauren Switzer, a teacher and orientation/mobility specialist, said the department works to identify the right tool for each student’s particular needs and goals, adding that the overall objective is for students “to have enormous tool kits to pull from in the right situation.”

The Vision Department includes two braillists, nine itinerant specialists/teachers, and vision technicians who travel to schools and conduct vision assessments. Some of the assisting staffers have had prior experience working with vision-impaired persons and wanted to continue to do so.

Taylor said she was an elementary teacher who worked with two children who had vision impairments, including one who was learning braille — “It blew my mind, and I just became interested in the process,” she said.

Switzer was pursuing a career in physical therapy but reconsidered after working with a woman who was blind. “I enjoyed how my brain had to work a little bit differently, I had to be more creative,” she said.

The work can also create a close bond with students. French, who makes materials in braille, has been invited to the weddings of former students.

Summer Tucker, Special Education Supervisor for KCS, said the work is rewarding in part because its impact goes beyond the classroom. You are giving students skills that are going to help them in life.

15Josh Flory is Communications Specialist for Knox County Schools.