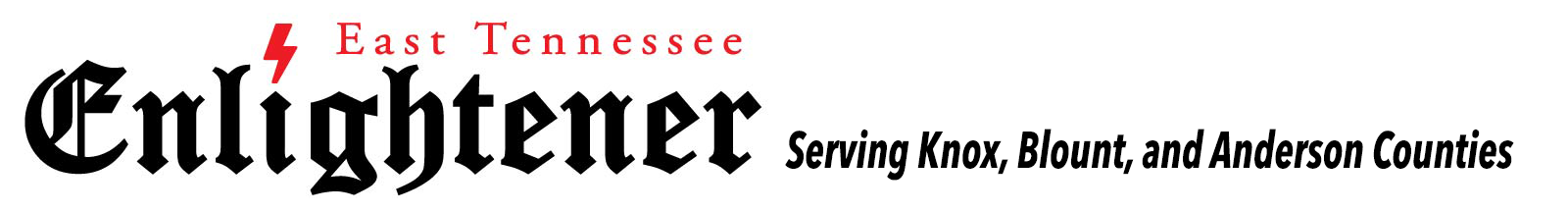

Vernon Jordan Remembered as ‘A Man in Full’

“Black people today, for all our righteous anger and forceful dissent, still believe in the American Dream. And we must, in this year of doubt and confusion, remind a forgetting nation that this land is ours, too. This nation too often forgets that this land is sprinkled with our sweat, watered with our tears, and fertilized with our blood … And so it is Black people who, by our belief in the ideals of American democracy, can help this nation to overcome its crisis of spirit and enter a new era of hope and fulfillment.” – Vernon E. Jordan, National Urban League Conference Keynote Address, 2010

Nationwide (March 9, 2021) – The National Urban League hosted a memorial service for one of the nation’s great champions of racial and economic justice. Vernon Eulion Jordan, Jr. (August 15, 1935 – March 1, 2021) died of natural causes at his home in Washington, D.C at the age of 85.

The NUL President Marc H. Morial honored his predecessor in saying, “The National Urban League would not be where it is today without Vernon Jordan. He was a man for others. Everywhere he went he was generous and unselfish in offering his time, energy and wisdom, to others. We send our prayers to his wife, Ann, his daughter, Vickee, and his entire family and extended family as we rededicate our commitment to his vision of justice and equality.”

Immediately after Jordan’s passing, the Howard University Board of Trustees announced the naming of the Law School Library as The Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Law Library in honor of the proud and devoted Howard alumnus, and Civil Rights icon upon the recommendation of Howard President Wayne A. I. Frederick.

“Vernon Jordan’s life embodied Howard’s motto of truth and service from his early beginnings as a lawyer to his work in the civil rights movement and later as an advisor to Presidents Reagan, Bush, Carter (also Obama) and most prominently as a friend and advisor to President Bill Clinton,” said President Wayne A. I. Frederick.

Jordan was born in an era when Black men in his native Georgia were routinely addressed as “Boy;” his mother pointedly nicknamed him “Man.” He honored her faith in him with his bravery, his grace, his brilliance, and his excellence.

Jordan conducted himself with exceptional poise and dignity with a striking presence standing at 6’4″ tall. As a child, he heard Thurgood Marshall speak at an NAACP meeting and immediately told his father, “I’m going to be a lawyer like Thurgood Marshall.”

Graduating in 1953 from the same segregated Atlanta high school that Martin Luther King, Jr., had attended years before, Jordan defied expectations by enrolling at the virtually all-white DePauw University in Indiana. It was the beginning of a life spent challenging the boundaries of where Black people belonged.

Said DePauw President Lori S. White: “Our community mourns the passing of Vernon Jordan, a member of the Class of 1957. He spoke loudly – through words and deeds – as a civil rights activist and quietly as a trusted counsel to presidents. DePauw is better for having had him as a beloved alumnus, and the country and the world are better for having him as a leader.”

While in college, Jordan worked as a chauffeur in the summer. His employer was amazed that he spent his breaks reading. The title of his memoir, Vernon Can Read, was inspired by that incident.

He entered Howard Law School at the height of the desegregation movement and quickly took his place on the front lines. He went to work for civil rights attorney Donald Hollowell, which successfully sued the University of Georgia for racial discrimination in its admission policies.

Jordan played an important role in desegregating education in the South. In the early 1960s, Jordan became the Georgia field director for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, director of the Voter Education Project of the Southern Regional Council, and executive director of the United Negro College Fund.

In 1961, he was at the front of escorting the first two Black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton E. Holmes, past a mob of howling white protesters to the admissions office at the University of Georgia.

“There were no thoughts about being afraid,” Jordan later said. This is what I went to law school to do — and I’m now here, doing it.”

Jordan served as Executive Director of the National Urban League from 1971 to 1981 and was a transformational leader who brought the movement into a new era. He was recruited after the unexpected drowning of Whitney M. Young in Nigeria; and just three years after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“It was a challenge to be walking in his (Whitney M. Young) shoes,” Jordan said. “After the losses of King and Young, and the turn towards conservatism that really began in the seventies, Black America was in a state of sadness, of disappointment.”

Jordan took the reigns of NUL at a pivotal moment in American history. It was immediately after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Fair Housing Act. The broad legal goals of the 20th Century Civil Rights Movement had been ‘legally’ achieved. As an attorney, Jordan saw his mission as empowering Black Americans to ‘realize’ the promise of these victories. In his words, “Black people today can check into any hotel in America, but most do not have the wherewithal to check out.”

After hearing no mention of the crises facing Black Americans in either President Gerald Ford’s State of the Union Address or Sen. Edmund Muskie’s response, Jordan produced the first State of Black America® report in 1976. Over the past 44 years, the State of Black America report has been the signature annual report from the National Urban League.

On May 29, 1980, Jordan was shot and seriously wounded outside the Marriott Inn in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Joseph Paul Franklin was acquitted of attempted murder charges. In 1996, Franklin was convicted of murder in another case and admitted to also shooting Jordan.

Former President Bill Clinton, a friend, noted in his eulogy that Jordan spent almost 100 days in the hospital — where he was visited by then President Jimmy Carter — after the 1980 shooting, and the wounds stayed with him for the rest of his life.

Mr. Clinton made him an informal White House adviser, a role Jordan continued as a confidant for former President Barack Obama.

After resigning from the Urban League in 1982, Jordan reinvented himself as a Washington insider and corporate influencer. He became a partner at Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer and Feld, and joined the New York investment firm of Lazard Freres & Co. as a senior managing partner in 2000.

“We have lost a great man today,” said Kim Koopersmith, chairperson of Akin Gump, calling Jordan “a wise and trusted mentor and friend who, in all that he did, inspired us to be the best possible version of ourselves.”

Jordan has received over 80 honorary degrees – including the University of Pennsylvania, where he delivered the commencement address to his daughter’s graduating class. But that speech only happened after Vickee Jordan gave her approval. She preferred he sit in the audience “like other dads,” before realizing that “he is not an ordinary dad.”

In the business world, Vernon was sought out to join corporate boards and advisory panels too numerous to name. In addition to being the president and chief executive officer of the National Urban League, Inc., he was also; executive director of the United Negro College Fund, Inc.; director of the Voter Education Project of the Southern Regional Council; attorney-consultant for the U.S. Office of Economic Opportunity; assistant to the executive director of the Southern Regional Council; Georgia field director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People; an attorney in private practice in Arkansas and Georgia; and served on the corporate board of many retail stores before becoming a partner emeritus at the Akin Gump law firm and a senior managing director at Lazard Frères & Co., a financial company in New York.

“His generosity was boundless, and his guidance was unassailable and delivered with a purposefulness and moral clarity that will never be equaled,” said Koopersmith of Akin Gump. “In so many respects, Vernon was one of a kind, and his enormous contributions — to our firm, to our country, and to us as individuals — will be greatly missed.”

Jordan was strategic about race issues. “My view on all this business about race is never to get angry, no, but to get even. You don’t take it out in anger; you take it out in achievement.” –Vernon Jordan, July 2000 in a New York Times interview.