Despite Diversity, Students Should Earn the Right to Belong

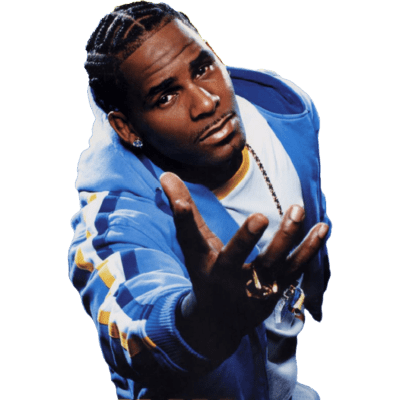

“I never want to be the token Negro.” – Taru Taylor has a message for black and brown high school graduates and college students.

By Taru Taylor, Guest Columnist

When I decided on law school, I aimed to meet, or exceed, the mean average Law School Admissions Test (LSAT) score wherever I chose to attend. Not that I took the LSAT seriously as a measure of “lawyerly” aptitude. But I understood its significance as a marker of merit.

I couldn’t afford a test-prep course, but I could afford some test-prep books. With only six weeks to prepare, I figured my best bet was to take a series of practice exams under simulated test-taking conditions. After 27 practice exams at my local library, the old college try paid off.

So I entered Case Western Reserve University School of Law in the fall of 2015 with my head up. With my LSAT and undergraduate achievements, ‘I was no token Negro.’ During a successful first year, I earned top marks and a recommendation from one of the leading

authorities on Ohio criminal law. While clerking at the Cuyahoga County Public Defender office during the summer and fall of 2016, I was no token Negro.

That same summer one of the co-deans of the law school personally asked me to participate in a photo-shoot for its “Law Admissions Viewbook.” I politely declined, citing camera shyness. But the deeper reason was that I didn’t want any part of “racial capitalism.”

Professor Nancy Leong, writing in Harvard Law Review, described it as the process where “a white individual or a predominantly white institution derives social or economic value from associating with individuals with nonwhite racial identities.” In other words, I refused the photo-shoot because I didn’t want to be a token Negro.

In contrast, last spring, I agreed to participate in a photo-shoot in recognition of my work as president of Case Western’s student chapter of the American Constitution Society (ACS).

ACS recognized me as one of its Next Generation Leaders and nominated me as one of four finalists to be the student representative on its board of directors. CWRU put my photo on its website to honor my Next Generation Leader distinction. I was on its website because of what I had achieved and not as a token Negro. Or so I thought.

Fast forward to the fall of 2017. Several classmates went to a local bar association luncheon in downtown Cleveland where they saw my photo advertising CWRU “diversity.” One of them photographed the ad and later texted it to me. If my classmates had not told me about the advertisement and shown it to me, I might never have known, nor seen, that I was CWRU’s unwitting token Negro. But there I was, the poster boy for the school’s brand of “diversity.”

Despite my accomplishments and expressed wishes, my university treated me as a commodity. It forced me into “racial capitalism.”

CWRU stripped my image from its context of honor and achievement and then recycled it for the school’s “diversity” commercial without

my consent. It was as if CWRU bamboozled me with the old bait-and-switch; as if it baited me into the Next Generation Leader photo, with the ultimate intention of using me as a token Negro.

In Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), a landmark affirmative-action case, Justice Clarence Thomas argued the following: “‘Diversity’, for all of its devotees, is more a fashionable catchphrase than it is a useful term, especially when something as serious as racial discrimination is at issue. Because the Equal Protection Clause renders the color of one’s skin constitutionally irrelevant to the Law School’s mission, I refer to the Law School’s mission as an ‘aesthetic’. That is, the Law School wants to have a certain appearance, from the shape of the desks and tables in its classrooms to the color of the students sitting in them.”

While (unlike Justice Thomas) I am for affirmative action as a means of redressing Black America’s unresolved grievances of slavery and Jim Crow segregation, I share his disdain for its “diversity” rationale. But please note the quotation marks. I am not against diversity, properly understood. I am for diversity that promotes equal opportunity, not recruitment of colored faces for a school’s aesthetic. I am for diversity that promotes equity, not racial capitalism; restitution, not tokenism.

When CWRU tokenized me, it made me wonder what was the point of all those practice exams and study sessions during my makeshift six-week LSAT boot camp. What was the point of making the Dean’s List, or of becoming an ACS Next Generation Leader? My school sees me as a token regardless, like I’m not here on my own merits. For a moment I

thought, what’s the point? But only for a moment.

My self-respect, my sense of honor, was, and is, the point. I should be able to look every single one of my classmates in the eye and say, “This is my house. I belong here.” That’s the point. It was never about demanding respect. The point has always been to command respect. To be a meritocrat, not a mascot.

That said, I’ll make my point in a different register this spring when I boycott my law school’s graduation ceremony. I mean to reclaim my dignity by refusing to be a fungible brown face of CWRU’s ceremonial aesthetic.

I am not your Negro. That’s the point.

Taru Taylor is the son of Knoxville, TN native, Ann Taylor who resides and raised him in the Washington/Maryland area.

(This article was first printed in The Observer campus newspaper of Case Western Reserve University. Note from The Observer editor: In 2017, the author contacted administrators who handled the Next Generation Leaders’ photoshoot. The administrators removed his picture from their archives.)

Black Excellence.