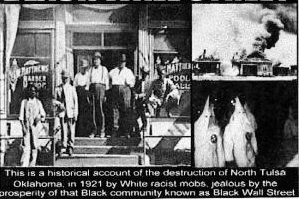

Greenwood: 1921 Black Wall Street Massacre

The 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed America’s wealthiest black neighborhood. The city was never the same.

American History – In 1921, Tulsa had the wealthiest black neighborhood in the country. On Sundays, women wore satin dresses and diamonds, while men wore silk shirts and gold chains.

In Greenwood, writes historian James S. Hirsch, “Teachers lived in brick homes furnished with Louis XIV dining room sets, fine china, and Steinway pianos.”

They called it Black Wall Street.

Developed on Indian Territory

Founded in 1906, Greenwood was developed on Indian Territory, the vast area where Native American tribes had been forced to relocate, which encompasses much of modern-day Eastern Oklahoma. Some African Americans who had been former slaves of the tribes, and subsequently integrated into tribal communities, acquired allotted land in Greenwood through the Dawes Act, a U.S. law that gave land to individual Native Americans. And many black sharecroppers fleeing racial oppression relocated to the region as well, in search of a better life post-Civil War.

O.W. Gurley, a wealthy black landowner, purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa, naming it Greenwood after the town in Mississippi.

J.B. Stradford, born into slavery in Kentucky, later becoming a lawyer and activist, moved to Greenwood in 1898. He built a 55-room luxury hotel bearing his name, the largest black-owned hotel in the country. An outspoken businessman, Stradford believed that blacks had a better chance of economic progress if they pooled their resources.

Greenwood was home to far less affluent African Americans as well. A significant number still worked in menial jobs, such as janitors, dishwashers, porters, and domestics. The money they earned outside of Greenwood was spent within the district.

It is said within Greenwood every dollar would change hands 19 times before it left the community.

A.J. Smitherman, a publisher whose family moved to Indian Territory in the 1890s, founded the Tulsa Star, a black newspaper headquartered in Greenwood that became instrumental in establishing the district’s socially-conscious mindset. The newspaper regularly informed African Americans about their legal rights and any court rulings or legislation that were beneficial or harmful to their community.

Greenwood was strictly segregated from the rest of the city, but still it flourished. It was home to black lawyers, business owners, and doctors — including Dr. A.C. Jackson, who was considered the most skilled surgeon in America and had a net worth of $100,000.

Dr. Jackson was killed on the night of May 31st, 1921, along with hundreds of black Tulsans. Thirty-five blocks of Greenwood were burned down that night. 1,256 homes and 191 businesses were destroyed. 10,000 black people were left homeless.

By morning, Black Wall Street had been reduced to rubble – in just 18-hours.“They had done everything that they were supposed to do in terms of the American dream,” says Carol Anderson, Professor of African American Studies at Emory University. “You work hard, you save your money, you go to school, you buy property. And this is what they had done under horrific conditions.”

In 1890, a group of migrants fleeing the hostile South settled an all-black town called Langston, 80 miles west of Tulsa. sdftawergfaresfesfresf Oklahoma wasn’t yet a state, and its racial dynamics weren’t set in stone. The architect of the settlement, Edwin McCabe, had a vision of Oklahoma as the black promised land. He sent recruiters to the South, preaching racial pride and self-sufficiency. At least 29 black separatist towns were established in Oklahoma during the late 19th century.

White homesteaders opposed to the “Africanization of Oklahoma” spearheaded a counter-movement, and the rural black settlements were all but wiped off the map. McCabe himself fled to Chicago in 1908. But black people were in Oklahoma for good, and they moved to the cities — taking that dream of empowerment with them.

Tulsa experienced a massive oil boom in the 1900s, and black residents began making good money as cooks and domestic servants to the freewheeling white nouveau riche. They invested that money in their own neighborhood, and by 1920 Greenwood was the most vibrant and affluent black community in the United States.

Tulsa experienced a massive oil boom in the 1900s, and black residents began making good money as cooks and domestic servants to the freewheeling white nouveau riche. They invested that money in their own neighborhood, and by 1920 Greenwood was the most vibrant and affluent black community in the United States.

White residents were disturbed by the growing black wealth in Greenwood, and sought to impose official segregation measures. In 1914, the city passed a law that forbade anyone from living on a block where more than three quarters of the preexisting residents were of another race. In isolation, Greenwood only thrived more. Its main strip boasted attorneys’ offices, auto shops, cafes, a movie theater, funeral homes, pool halls, beauty salons, grocery stores, furriers and confectioneries.

One entrepreneur built an elegant 54-room hotel, likely the largest ever owned by a black person in pre-Civil Rights America. Crystal chandeliers hung from the ceiling in the banquet hall. Its owner, J.B. Stradford, had been born a slave.

“That resentment in Tulsa was so intense,” says Carol Anderson, “it was just waiting for a spark in order to ignite it.” That spark was a sexual assault allegation against a black teenager named Dick Rowland. It’s not entirely clear what happened in the elevator of the Drexel Building on May 30, 1921, but one common narrative is that Rowland accidentally tripped against its operator, a white 17-year-old named Sarah Page, causing her to scream.

A bystander who heard the scream called the police, and “like a game of telephone, the story became more inflammatory with each retelling, and spread rapidly,” writes Dexter Mullins.

When Rowland was captured, a few black World War I veterans from Greenwood armed themselves in front of the courthouse, prepared to prevent a lynching. They were justified in their fear — a man named Roy Belton had been lynched in Tulsa the year before, after his arrest. “The lynching of Roy Belton,” read Greenwood’s black newspaper The Tulsa Star in 1920, “explodes the theory that a prisoner is safe on the top of the Court House from mob violence.”

When Rowland was captured, a few black World War I veterans from Greenwood armed themselves in front of the courthouse, prepared to prevent a lynching. They were justified in their fear — a man named Roy Belton had been lynched in Tulsa the year before, after his arrest. “The lynching of Roy Belton,” read Greenwood’s black newspaper The Tulsa Star in 1920, “explodes the theory that a prisoner is safe on the top of the Court House from mob violence.”

In front of the courthouse where Dick Rowland was being kept, a group of white men approached the black men from Greenwood. “Nigger, what are you going to do with that pistol?” said one.

“I’m going to use it if I need to,” the black man replied.

The white man attempted to wrest the pistol from his hands, and a gunshot rang out. It’s unclear whether it was accidental, a warning shot, or an attempt to injure or kill. In any case, all hell broke loose.

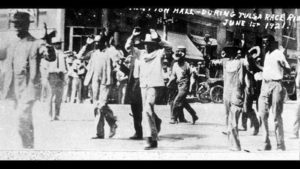

The groups of white and black men had a running gunfight all the way to Greenwood. When they got there, the group of whites — which had grown in number — began firing indiscriminately on black bystanders. Black people were shot in the streets, lynched, and dragged behind cars with nooses tied around their necks. The militia looted the homes and businesses before burning them down.

The groups of white and black men had a running gunfight all the way to Greenwood. When they got there, the group of whites — which had grown in number — began firing indiscriminately on black bystanders. Black people were shot in the streets, lynched, and dragged behind cars with nooses tied around their necks. The militia looted the homes and businesses before burning them down.

Greenwood residents returned gunfire, but the white mob was larger and better armed. Airplanes were also deployed that opened fired and drop explosives. Most of Greenwood was burned to the ground. About 6,000 of those lucky enough to escape death were held as prisoners, a fate none of the white rioters had to deal with.

In the aftermath, 35 square city blocks were burned to the ground. The destruction took 600 businesses, 21 churches, a hospital, a bank, a post office, a bus system, a school system, 21 restaurants, 30 grocery stores, 2 movie theaters, libraries, law offices, doctor and dentist offices, a taxi service, 6 private air crafts, and more than 1,256 homes perished.

An eye witness account by a black lawyer Buck Colbert Franklin, reads: “Smoke ascended the sky in thick, black volumes and amid it all, the planes — now a dozen or more in number — still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air… The sidewalks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls.”

An official report published by the city in 2001 confirmed that some of the planes were flown by police conducting reconnaissance. The others, it concluded, were probably piloted by white civilians who fired ammunition and dropped bottles of gasoline on the buildings below.

In the middle of the night, the Tulsa police formally requested that the National Guard assist them in quelling what they called a “Negro uprising.” As they awaited the National Guard, they let Greenwood burn.

When the soldiers arrived, they detained 6,000 black residents, many of them for more than a week. Upon release, these residents were homeless. In 2016 numbers, more than $30 million worth of property damage was sustained.

“Tulsa civic leaders clung to conservative estimates,” writes historian Tim Madigan, but “the number of the dead no doubt climbed well into the hundreds, making the burning in Tulsa the deadliest domestic American outbreak since the Civil War.”

After the massacre, Greenwood was uninhabitable. Former residents lived in Red Cross tents for months, through the freezing winter.

The Tulsa Real Estate Exchange attempted to make it prohibitively expensive to rebuild Greenwood. A founder of Tulsa named W. Tate Brady — also a Klansman — had taken control of the Exchange, and devised a plan to relocate black residents even further away from the city center. The Exchange prepared building codes to make the area industrial instead of residential.

But even with everything in ruins, former Greenwood residents fought back. Buck Colbert Franklin took the case to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which declared the city’s efforts to forestall redevelopment unconstitutional.

Tulsa’s black population set about rebuilding, and it held on for a few more decades. But Greenwood was never the same. In the 1970s, much of it was leveled to make room for a highway.

The official investigation in 2001 found the city partly responsible for the casualties and property damage of the Tulsa massacre. In its section “Assessing State and City Culpability,” the report mentions not only the passivity of police, but their active involvement in the mob violence. It reads, “Tulsa failed to take action to protect against the riot. More important, city officials deputized men right after the riot broke out. Some of those deputies — probably in conjunction with some uniformed police officers — were responsible for some of the burning of Greenwood.”

The 2001 report concluded that the City of Tulsa owed reparations to the survivors of the massacre and their descendants. Those reparations have yet to be paid.

The survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre are nearly all dead now. And the mob violence they endured not only traumatized them as individuals — it destroyed black wealth in Tulsa, and set the parameters for race relations in the city for the next century.

“Black success was an intolerable affront to the social order of white supremacy,” writes Hirsch, “so taking their possessions not only stripped Blacks of their material status, but also tipped the social scales back to their proper alignment.” In Tulsa today, as elsewhere, that alignment remains strikingly unequal.

History shapes the world around us — from national elections to cultural debates to marches in cities across the country. Knowledge of the past helps to shape a better future.