A Freedman’s Response to His Tennessee Master’s Request to Come Back

AMERICAN HISTORY

THAT TIME JORDAN ANDERSON SENT HIS “LETTER FROM A FREEDMAN TO HIS OLD MASTER”

– During the 19th century, there were many freed slaves that went on to lead extremely noteworthy lives despite all the adversity they faced in their lifetime, such as the world-famous Frederick Douglass, who not only played an important role in fighting for black people’s rights but also championed women’s rights, particularly playing an important part in the fight for the right for women to vote. Not everyone can be so accomplished as the great Frederick Douglas, but that doesn’t mean they don’t at times do noteworthy things.

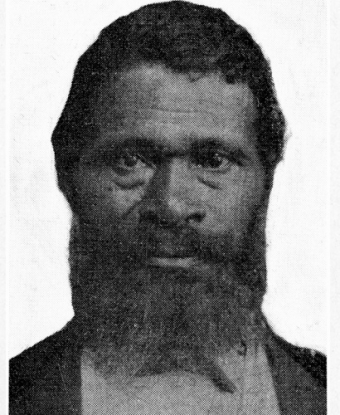

This brings us to the subject of – Jordan Anderson, a former slave who received a letter from his former master requesting he come back to work. Jordan’s reply was a deliciously satirical letter in which, when reading between the lines, he essentially told him in the most polite and eloquent way possible to kiss his derriere. Widely published throughout the United States and parts of Europe, the response made Jordan a media darling overnight.

Given his background as a slave, we unsurprisingly know very little about Jordan’s life prior to being taken from his parents and sold as a boy. What little historians have managed to piece together is that Anderson was born in December of 1825 “somewhere” in Tennessee. In fact, we know so little about Jordan that we’re not even sure if that’s how he actually spelled his first name, since it’s written as “Jourdan” on some documents, such as an 1870 federal census of Dayton Ohio where he lived at the time, and “Jordan” on others.

Historians are confident that Jordan was sold into slavery at around age 7 or 8 to one General Paulding Anderson. Anderson then took Jordan and gifted him to his son, Patrick, who went by his middle name, Henry, for most of his life. Exactly what role Jordan served during his formative years isn’t clear, but we do know that at the time it was common for slave owners to give their children similarly aged slaves to function as servants who doubled as playmates; so it’s likely Jordan served such a function for Henry who was around his age.

As he grew into a man, Jordan took a more active role on the Anderson family plantation in Big Spring, Tennessee, apparently becoming one of Henry’s most reliable and able workers. At an unknown point in time in 1848 while working on the plantation, Jordan married a fellow slave named Amanda McGregor with whom he eventually sired 11 children.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, Jordan’s life changed very little and he still continued to dutifully work the plantation for his master with his wife until one fateful day in 1864 when Union Soldiers happened upon the plantation. Upon encountering Jordan, the soldiers granted him, his wife and children their freedom, making the act official with papers from the Provost Marshal General of Nashville, documents Jordan would treasure for the rest of his life.

Upon being granted his freedom, Jordan immediately left the plantation which angered Henry to such an extent that he shot at Jordan as he was leaving, only ceasing to fire when a neighbor grabbed Henry’s pistol from him. Reportedly, Henry vowed to kill Jordan if he ever set foot on his property again.

Following his departure from the plantation, Jordan worked briefly in a Nashville field hospital, becoming close friends with a surgeon called Dr. Clarke McDermont. When the Civil War ended in 1865, McDermont helped Jordan and his family move to Dayton, Ohio and put him in contact with his father-in-law, Valentine Winters, an abolitionist who helped him secure work in the town.

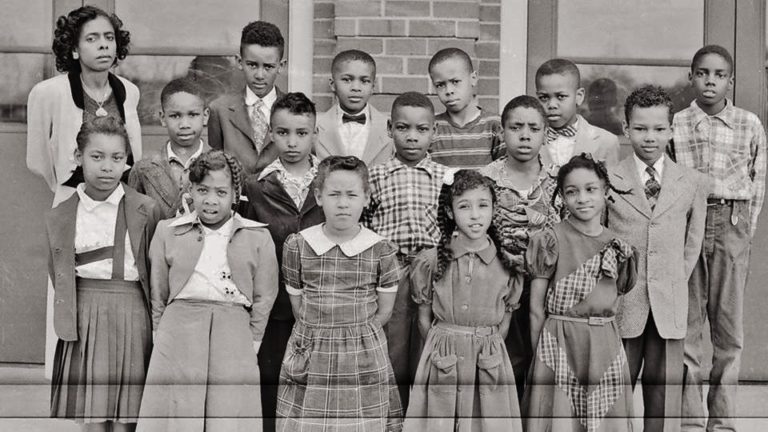

For the most part, Jordan’s life in Dayton was uneventful, with his time spent working with a stoic sense of quiet dignity, supporting his family and making sure his many children received a good education, something the illiterate Jordan was never given the opportunity to have. (In fact, it was noted that while still a slave, when an unspecified white girl tried to teach one of his children to read, the girl was beaten for it and forced to stop.)

Jordan’s quiet life was briefly shattered in July of 1865 when out of the blue he received an urgent letter from his former master, Henry. As Jordan couldn’t read, he took the letter to Valentine Winters and asked him to read it to him. As it turns out, following the Civil War, the Anderson Plantation had fallen into complete disrepair, as is wont to happen when your entire workforce leaves pretty much all at once. Deeply in debt, in a desperate attempt to save himself from total financial ruin, Henry reached out to the only man he knew who not only had the skills needed for the harvest, but also potentially the clout to convince some of the other slaves to return for paid work- Jordan Anderson. The letter also promised that Jordan would be paid and be treated as a free man if he returned.

At this point, most people would have screwed up the letter and thrown it in the trash while taking some sordid satisfaction in that karma was doing its job, but Jordan had a better idea. After several days of pondering the letter’s contents, he invited Winters to his home and dictated an exquisite response:

“Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.

I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. (About $178,000 today) Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq.,[267] Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.”

At Jordan’s behest, Winters sent the letter to Henry with the simple, informal title, “Letter from a Freedman to His Old Master”. Winters later had the letter published in an edition of the Cincinnati Commercial with the same title. The letter proved to be immensely popular, both because of the sheer level of snark displayed and the eloquence with which Jordan had told off his former “boss”. The letter was later reprinted in papers across the country and even published in parts of Europe, making Henry a world-renowned laughing stock.

Unsurprisingly, Henry never took Jordan up on his offer to pay him 50 years of wages in one go and the letter likely stopped any of his other slaves being tempted back when he wrote to them as well. As a result, the crops that year were never harvested. Henry, deeply in debt, had to sell the plantation for a fraction of its worth and he died penniless and destitute a few years later at age 44.

As for Jordan, he lived and worked in Dayton for the rest of his long life, dying at the age of 81 in 1907.