Remains of WWII Tuskegee Airman Buried with Honors

Seventy-five years after his fighter plane crashed in Austria, Tuskegee Airman Capt. Lawrence E. Dickson was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery on Friday, March 23, 2019. Air Force jets roared overhead and his 76-year-old daughter, Marla L. Andrews, received a folded flag from an Army general who knelt before her as his grandchildren looked on.

At an earlier church service, the Rev. Jerry Sanders of Fountain Baptist Church in Summit, N.J. likened Dickson to the Old Testament patriarch Joseph, whose bones were carried by his people to the Promised Land from the foreign realm where he died.

“Joseph served his people on foreign soil,” said Rev. Sanders. “What we do for Captain Dickson today is what they did for Joseph in the long ago.” It was a solemn farewell for a daughter who cherished a father she never knew and who lamented the life she might have had.

“I don’t think I would have felt so empty and so alone,” Andrews, of East Orange, N.J., said Thursday. “I heard many people say that he was very friendly, he was very warm, he was extremely personable,” she said. “I just had the feeling that if he would have lived, it would have been so different. But he didn’t.”

In July, the Defense Department announced that it had accounted for Dickson, who was among more than two dozen black aviators known as Tuskegee Airmen who were still missing from World War II.

Dickson, who was 24 when he went down, joined the Army Air Forces from New York and was a member of the 100th Fighter Squadron, 332nd Fighter Group. He trained at the Tuskegee Army Flying School and crashed in mountainous southern Austria on Dec. 23, 1944, while on an escort mission.

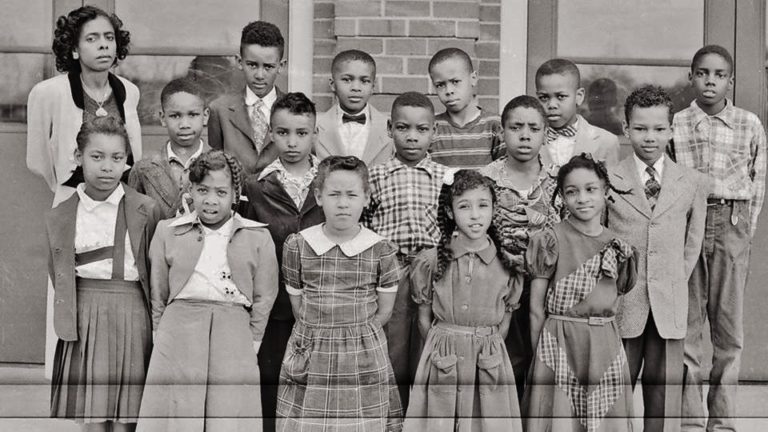

He was among the more than 900 black pilots who were trained at the segregated Tuskegee airfield in Alabama during the war. They were African-American men from all over the country who fought racism and oppression at home and enemy pilots and antiaircraft gunners overseas.

More than 400 served in combat, flying patrol and strafing missions and escorting bombers from bases in North Africa and Italy. The tail sections of their fighter planes were painted a distinctive red.

During the service in the Old Post Chapel at Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall, Sanders spoke of the Israelites’ escape from slavery, comparing it to men such as Dickson helping African Americans on their exodus from bondage.

“Remember your future is based on my past,” Sanders said Joseph reminded his people.

“Where you’re going has something to with where I’ve been,” he said. “The bones of Joseph, like the bones of Captain Dickson, tell a story.”

During a dig in 2017 at the crash site, near Hohenthurn, Austria, a ring belonging to Dickson was found in the dirt by a University of New Orleans graduate student, Titus Firmin.

Charred remains and other small personal items were also found, along with parts of the airplane.

Last August, the Army presented Andrews with the ring and a formal report on how her father was accounted for.

The 14-karat art deco ring was a precious physical link.

There had been talk for months that a ring had been found during the dig. When an official gave it to her in her home, she said quietly, “Wow, guys.”

The excavation had also found the ring’s aqua-colored stone, which had broken loose and was found separately.

The ring was inscribed: “P.D.,” with a heart with an arrow through it, and “L.E.D. 5-31-43.”

P.D. was Andrews’ mother, Phyllis Dickson. L.E.D. was her father, and May 31, 1943, was his 23rd birthday.

The Army also gave her a remnant of a harmonica that was found at the crash site, and a small cross.

The identification had been confirmed when DNA was extracted from arm- and leg-bone fragments found at the crash site and matched with DNA from Andrews, a nephew and a distant cousin.

The dig in 2017 was conducted by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, the University of New Orleans and the University of Austria at Innsbruck, with help from the National World War II Museum in New Orleans.

There are 26 Tuskegee Airmen still missing from the war.

Two days before Christmas 1944, Dickson took off from his base in Italy in a P-51D Mustang nicknamed “Peggin,” headed for Nazi-occupied Prague.

He was on his 68th mission and had already been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for meritorious service.

He was leading a three-Mustang escort of a fast but unarmed photo reconnaissance plane, according to the account of a wingman, 2nd Lt. Robert L. Martin, many years later. (Martin died July 26, 2018, at the age of 99 at his home in Olympia Fields, Illinois. His daughter, Gabrielle Martin, was present for Friday’s service.)

The four planes headed over the mountains for Prague. About an hour into the trip, Dickson radioed that he was having engine trouble and began losing speed.

His wingmen stayed with him as he dropped back. The twin-engine reconnaissance plane sped on and was soon out of sight.

Dickson decided to turn for home in his crippled plane, and his buddies stuck with him.

He looked for a spot to land or bail out. Martin saw him jettison the canopy of his cockpit before bailing out, but then he lost sight of the airplane.

The two wingmen circled, looking for a parachute, a column of smoke or burning wreckage.

There was nothing but an empty, snow-covered valley.

After the war, the Army searched for Dickson in northern Italy, where Martin thought he went down. Other crashed planes and remains were found, but not his.

In 1949, the Army recommended that his remains be declared “nonrecoverable.”

In 2017, the Pentagon, armed with new data on the crash location, began investigating the case anew.

“We need to have more reverence for the bones,” Sanders said Friday. “There are some things we can learn from bones. There is a … blessing in the bones. We need to remember those who have gone before.”